Who realises that the history of the smartwatch also runs through Switzerland? It is an overlooked adventure blending elite sport, engineering, and patent strategy. From Sion to Texas, via laboratories and training grounds, this is the story of how innovations from Switzerland quietly helped fuel the revolution in connected devices a lesson in entrepreneurship balancing technological passion with economic realism.

The story begins far from the traditional watchmaking workshops. On a training field, Patrick Flaction observes bodies in motion. A specialist in physical conditioning, he has grown dissatisfied with relying solely on his eye and his stopwatch. He wants data. Certainty. “At the time, if you really wanted to measure performance, you had to send the athlete to a laboratory. It was slow, expensive, sometimes complicated. So I wanted to bring the laboratory to the training ground.”

This ambition would change everything. For behind this quest for precision lies one of the most remarkable Swiss technological adventures of recent years a story of passion, innovation… and missed opportunities.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

When Technology Arrives on the Field

To measure better is to train better. Patrick Flaction who notably coached ski champion Lara Gut knows this well: every hundredth of a second matters when you are training the world’s elite. Having data makes it possible to fine-tune effort, prevent injuries, and capture what the eye cannot see.

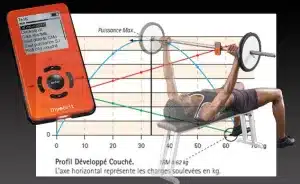

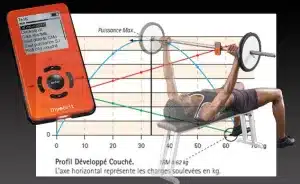

His friend, Manu Praz, suggests he approach the School of Engineering in Sion for initial tests. But the real turning point comes with his encounter with Frédéric Koehn and Alain Nicod passionate investors and with Alex Bezinge, an engineer as impulsive as he is talented. Together, they patent a small device worn on the hips, capable of measuring force, speed and power in real time in other words, a truly miniaturised biomechanics laboratory.

Myotest is born in Sion. Success is immediate. At the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, a rumour spreads through the Olympic Village: more than 30% of the athletes are said to be training with this little Swiss device.

When Technology Arrives on the Field

To measure better is to train better. Patrick Flaction who notably coached ski champion Lara Gut knows this well: every hundredth of a second matters when you are training the world’s elite. Having data makes it possible to fine-tune effort, prevent injuries, and capture what the eye cannot see.

His friend, Manu Praz, suggests he approach the School of Engineering in Sion for initial tests. But the real turning point comes with his encounter with Frédéric Koehn and Alain Nicod passionate investors and with Alex Bezinge, an engineer as impulsive as he is talented. Together, they patent a small device worn on the hips, capable of measuring force, speed and power in real time in other words, a truly miniaturised biomechanics laboratory.

Myotest is born in Sion. Success is immediate. At the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, a rumour spreads through the Olympic Village: more than 30% of the athletes are said to be training with this little Swiss device.

![Slyde Watch[46]](https://www.patentattorneys.ch/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Slyde-Watch46.png)

The Strategic Shift

But manufacturing is expensive, and volumes remain modest. By 2016, the company needs fresh momentum. It finds it in the form of Christophe Ramstein, an experienced executive well versed in restructuring. “I’m a transition CEO,” he explains. “I enter a company, review the strategy, raise funds, restructure… and then move on.”

For Myotest, the diagnosis is clear: producing hardware is too complex and too costly. Every stage production, distribution, marketing demands considerable resources. The company must capitalise on its true value: its technology.

“We packed away the hardware and licensed our solution to the giants,” summarises Christophe Ramstein. The team then develops exceptionally precise biomechanical running-analysis software. In 2019, major industry players parade through the offices in Sion, all saying the same thing: “We don’t know how you do it, but you are by far the most accurate.”

Myotest’s software becomes integrated into several of the world’s best-selling smartwatches. Yet the company’s economic balance remains fragile.

Slyde Watch: the Horological Dream

Meanwhile, another story is taking shape. Renowned Swiss watchmaker Jorg Hysek, accompanied by Pascal Pozzo di Borgo, presents an audacious project to Alain Nicod. They have the idea, the ambition, the designs… but not the manufacturing capacity.

Very quickly, Alain Nicod and Alex Bezinge decide to take on the challenge: to create a luxury smartwatch, halfway between jewellery and technological feat. It is exactly the kind of undertaking they love complex, demanding and ambitious.

Eighteen months of intensive development follow. Prototyping, testing, material selection, electronic optimisation: everything is imagined, reconsidered, refined. The watch is launched in 2011 (four years before the Apple Watch!) and the result exceeds even the most optimistic expectations. Elegant, innovative, desirable, the watch captivates. The first pieces quickly find buyers, even as far as Russia and Ukraine.

Then tragedy strikes. Alex Bezinge dies suddenly in a microlight accident. With him, a vital part of the project’s energy disappears. “Alex’s death, the lack of resources, and the silence of the Swiss watchmakers when we offered them our expertise… all of that convinced us to move on,” confides Alain Nicod.

It is the end of the Slyde Watch. With this project disappears the dream of a smartwatch made in Switzerland..

Christophe Ramstein

Alain Nicod

Heading to Texas

The story doesn’t end there. Christophe Ramstein, Alain Nicod and Christophe Saam founder of P&TS and in charge of patent strategy since the very beginning reach the same conclusion: their companies hold a treasure. Myotest and Slyde Watch have developed technologies now integrated into almost all smartwatches worldwide. Their advantage? A solid portfolio of patents that effectively protects these pioneering innovations.

The next chapter unfolds across the Atlantic. In Texas, a new company is born, with a clear objective: to acquire all the patents, identify the right counterparts, and negotiate directly with the tech giants.

Today, many smartwatch wearers have on their wrists inventions created in Switzerland at Myotest and Slyde Watch even if mass production happens elsewhere.

The Swiss Lesson

This story also reveals the limitations of a small country which, despite its recognised capacity for innovation, struggles to mobilise the resources needed for large-scale production. Industrialising, delivering worldwide? It requires colossal means and a domestic market which, in Switzerland, simply does not exist.

“We too often believe that innovation depends on manufacturing,” says Christophe Saam. “Start-ups dream of factories, of full order books, of finished products shipped to every corner of the world. Sometimes it is more effective to focus on creating intellectual property.”

A valuable lesson for the start-up ecosystem: selling patented technology to players better equipped to manufacture and distribute on a massive scale can prove faster and less risky than producing and marketing directly. In such cases, intellectual property becomes the product.

Christophe Saam, specialist in patents and intellectual property, Neuchâtel, 5 November 2021. Photos © Guillaume Perret / Lundi13

Christophe Saam, specialist in patents and intellectual property, Neuchâtel, 5 November 2021. Photos © Guillaume Perret / Lundi13Christophe Saam — P&TS, patent strategy